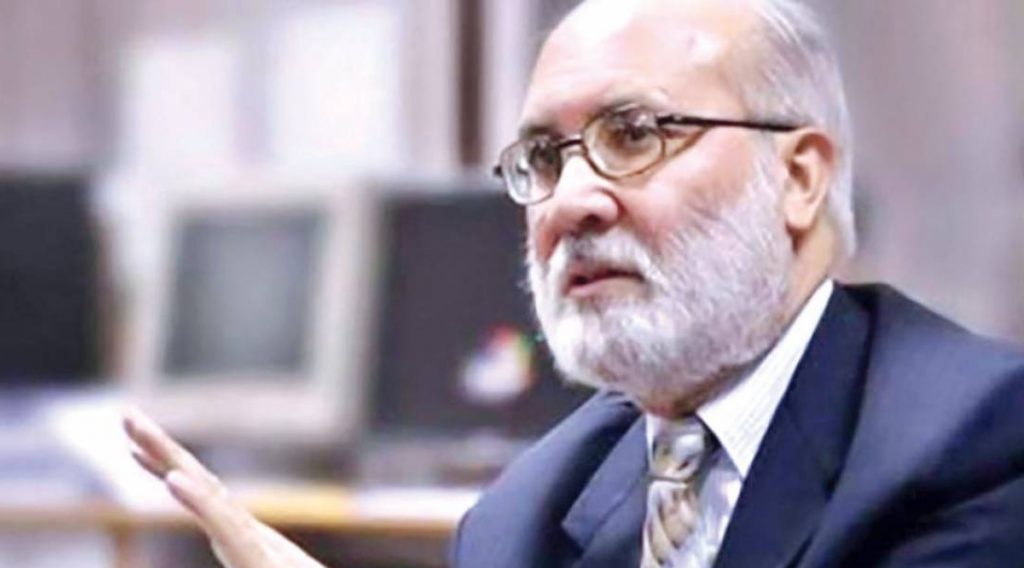

The death of Rahimullah Yusufzai is a terrible blow to journalism – not just in this region, but at a global level. He was one of the best-known and most well-respected journalists on the subject of the Afghan conflict and considered an authority on the Taliban and Al-Qaeda. With his passing we have lost not just an important source of context and information, we have lost a master practitioner of this craft, somebody who was dedicated to truth and accuracy, and who was always ready to go into the field, talk to people, find the story, understand the context.

Despite his considerable fame, Rahimullah sahab, as we always called him, remained modest about his achievements and very down to earth about everything. What I most remember about him was his enthusiasm for his work and the professionalism with which he did it. In the three decades, I knew him, he never turned down a request for an interview or a story – even if this was a very short notice.

Rahimullah sahab was recommended to Newsline in 1989 by another journalist (I think it was Aziz Siddiqui, then editor of the Frontier Post). At that time, he worked for the Frontier Post in Peshawar and Rahimullah sahab would file the monthly political roundup from the province for us. His copy was impeccable and his political insights sound but what was also very interesting was his readiness to write on other subjects. We would ask about possible writers or reporters for sports and culture stories and he would offer to do everything himself. I remember a few responses like: “Sports – that’s my first love! I can do that for you,” and “Culture, I can cover that for you.” And he really could. He was extremely versatile; a story he did on Pashto cinema was one of Newsline’s greatest hits.

Newsline, founded by Razia Bhatti, was an independent, journalist-owned venture and we often struggled with finances but Rahimullah sahab was a great supporter in those early years and he remained so throughout his life. In March this year – just six months ago – he was a guest speaker at the IBA Centre for Excellence in Journalism’s Razia Bhatti Memorial lecture. It was indeed a privilege to have him deliver the lecture in which he spoke specifically about his 1998 interview with Osama bin Laden (OBL) and more generally about reporting on the Taliban and Al-Qaeda.

The event was titled ‘Tea with Osama bin Laden’, and despite being a virtual event, it was extremely well attended. After Kamal Siddiqui of CEJ, Akbar Zaidi of IBA and I had said a few introductory words, Rahimullah sahab began his talk by saying how “humbled and honoured” he was by what had been said. We had only stated facts and talked about his achievements and reputation. I had also spoken about his great sense of professional solidarity, but the fact that he was so touched by what we said showed how modest he remained about his achievements.

The talk itself was extremely interesting and full of detail. His account of a 1998 presser with OBL was fascinating. He recalled that he asked OBL a number of awkward questions, one of which was how wealthy was he. In response, OBL had put his hand on his heart and said he was rich (‘ghani’) in there and thus deflected the enquiry. There was a lot of interesting detail in his account of the OBL interview, which took place a few months after the press briefing — how it was arranged, what constraints there were, how he was asked to destroy a photo he took of OBL entering the tent because Osama bin Laden was walking with the aid of a stick and the organisation “didn’t want him to look weak”.

In the Q&A session after the talk, Rahimullah sahab also spoke about a number of other experiences and issues. When asked about any advice he wanted to remind journalism students of, he said the most important issues were just “hard work and honesty”. He emphasised the need for proper preparation and research (tayari). He also said laughingly that he was perhaps the person who had taken the most photographs of OBL but that in the early years, he had sold them to various outlets, not for very much money. That sounds right, Rahimullah sahab was very much a person who wanted to get on with his work rather than promote his own persona or negotiate lucrative deals for his work.

We also talked about the Sharbat Gula matter. Sharbat Gula was the green-eyed Afghan girl whose photograph had appeared on the cover of National Geographic in 1984, and who was featured again by the publication more than a decade later (and who Pakistan, rather pointlessly, deported in 2016 despite her having lived in the country for decades). Rahimullah sahab was the person who traced her for National Geographic after all those years and he spoke about that and how he was able to negotiate with the publication on her behalf. He needn’t have done that — many journalists would have looked only to their own interests but Rahimullah sahab made sure to help Sharbat Gula’s family to get something from the magazine (medical aid, Hajj expenses, and a small monthly stipend). He said he had never mentioned all of this publicly before but now he was putting it into his book. When asked when we might see this book completed, he lamented he wasn’t able to give enough time to this because the misfortune of a working journalist like himself was he was always so involved with various deadlines on a daily basis. He also mentioned the financial pressures journalists in Pakistan were facing and how his employers had not paid their staff for months.

He recalled that a CNN producer who had once interviewed OBL had managed to produce two books based just on that one meeting and how so many others who had met Osama had managed to get so much mileage out of the experience. He said somehow the fascination with the man and the movement continued, yet he himself had not really taken advantage of this, but that he would record such experiences in his book.

But now Rahimullah sahab is gone. We don’t know if any part of his book is complete or whether it was in notes and planning form. But he does leave behind a vast body of work in journalism. He is now invariably described as a ‘veteran’ journalist, which is apt: he covered the Afghan conflict for years and interviewed nearly every Afghan leader of consequence, including Dr Najeebullah and several leading mujahideen. He had a rare insight and understanding of the politics of his own country and province. He leaves behind a tremendous void – not just was he an experienced reporter and an informed analyst, he was an invaluable source of information and one of the people still practising the craft of journalism with integrity and commitment.

Apart from his enthusiasm for his work, his meticulous attention to detail and fact-checking, and his ability to present a balanced and factual picture, what I shall remember also about Rahimullah sahab is the tremendous grace and dignity with which he always conducted himself – whether on reporting assignments, in international conferences or in small villages. He was never one to curry favour or be impressed by pomp or power. He always remained essentially a journalist: looking for stories, talking to people, ascertaining the facts, and abiding by the basic principles of journalism.

Rahimullah sahab towered above most of his colleagues physically in his life but professionally too, he was a giant of the profession. We shall all miss him very much.