After the inauguration of the Kartarpur Corridor in November 2019, Pakistan has repositioned itself as an attractive destination for the global Sikh community for religious tourism. The numbers so far have not reached the expectations because of many reasons including among others the spread of the coronavirus and the heightened tension between India and Pakistan.

Despite many hurdles, the history of the land of Pakistan retains a rich potential for the Sikh diaspora to relive and reclaim their religious heritage. As an effort to highlight and elaborate the religious memorials, Gurdwara, and history of the important religious figures, we find an impressive effort of Dr Dalvir S. Pannu as, The Sikh Heritage: Beyond Borders of India and Pakistan.

The book is both a culmination of the writer’s ten years journey to explore the present condition of the memorial sites, also beautifully presented pictorially in it and a search for the authentic Sikh history with the help of archival and contemporary sources. The book also engages with the historical interaction between Muslims and Sikhs before 1947.

To tell the story of eighty-four memorials in six districts of Punjab, the book sets off from the description of the Gurdwara Janam Asthan (the birthplace of Guru Nanak, the first of the ten Sikh Gurus), in the Nankana district.

Locating 13 more in Nankana, 03 in Sheikhupura and six in Sialkot, the book highlights the importance of Guru Nanak’s life to understand the development of Sikhism. One finds that Gurdwara Sacha Sauda in Sheikhupura commemorates the moment in Guru Nanak’s life when he gave twenty rupees to a group of hungry mendicants instead of using them for personal business purpose. The Gurdwara Babe Di Ber in Sialkot the meeting of Guru Nanak with a Muslim mystic whose anger with the locality was resolved by Guru by pointing out the importance of being forgiving.

Dr Pannu could locate the dilapidated remains of 17 memorials in the Kasur district. The remains of the memorials still exhibit dimly the frescoes on the walls and ceilings, paintings of the saints, dilapidating arches, inscriptions in Gurmukhi, and weakened parapets.

The book surprises its local Muslim reader with the recollection of the story of Baba Bulle Shah (1680-1757) taking refuge in a Gurdwara Sahib of Daftuh, the Union Council of the Kasur district. The famous poet, and later Sufi saint of the Muslims, took refuge in the Gurdwara to save his life from the angry Muslim mob of village Pandoke, his ancestral village.

The shared communal traditions engulf the reader further once the book ferrets out the shrines and memorials in Lahore. The half of the total number of Sikh shrines, the book mines them in Lahore highlighting the importance of the city not only as a center stage for the development of the Sikh religion but also for being a witness to a long history of mutual engagement, strife, and coexistence of Sikhs and Muslims.

One comes to know that Lahore is the birthplace of the sister of Guru Nanak and first GurSikh Bebe Nanki (1464-1518) in a village Chahal memorialized as Dera Chahal, and Guru Ram Das (1534-1581), the fourth of the ten Sikh Gurus, memorialized as Gurdwara Janam Asthan Guru Ram Das.

Lahore also became a place where a Mughal ruler martyred Guru Arjan (1563-1606), the fifth of the ten Sikh Gurus, and the site is memorialized as Gurdwara Dehra Sahib. The city has the site of Gurdwara Shaheed Ganj, memorialized as a site of a painful memory of Sikhs killed in hundreds during the period of Mughal Viceroys of Lahore, including Abdul Samad Khan (1713-1726), Zakariya Khan (1726-1745), and Mir Mannu (1748-1753).

The same city is also important for the shrines of figures including Pir Sheikh Abdul Qadir Jilani Sani (d. 1560), Wazir Khan (Sheikh Il mud Din Ansari, famous for making a grand mosque) and Hazrat Mian Mir (1550-1635), radiating the cheerful memories of friendly and intellectual interaction with Sikh Gurus.

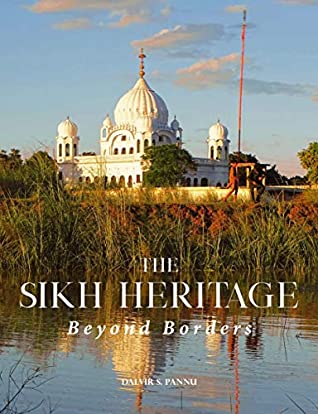

The book ends its journey in the Narowal district at the Gurdwara Darbar Sahib, Kartarpur (God’s dwelling). The story of Gurdwara Darbar Sahib is also the story of the last eighteen years of the life of Guru Nanak who finally settled in this village and favored the life of the household instead of Udasis or life as a Divine Mission.

As the book collected its data before 2019, the story of the Gurdwara Darbar Sahib does not include the development of the site as a Gurdwara Kartarpur Corridor inaugurated in November 2019. However, the details of Guru Nanak’s household life introduce the reader with interesting anecdotes coloring Sikhism with the teachings of Guru in a more practical fashion.

The book is an outcome of the authentic and deep-seated urge to find one’s own identity in the communally divided region.

In the backdrop of the birth of Pakistan that entailed violent communal clashes resulted in the uprooting of almost 2 million Sikhs from the region of Pakistan and constant tension on the borders between India and Pakistan since then, there has been seldom space, especially during the whole twentieth century for conducting such a study.

This book is a witness to the beginning of a new turn in the history of Pakistan, when, instead of bracketing with the victims or perpetrators communally, the painful memories of violence can be commemorated from the humanistic perspective. The search of the Global Sikh community for the Sikhism within this region may become an opportunity for Pakistan to embrace its own heritage truly.